| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 37. . . .May 27, 2016

excerpt:

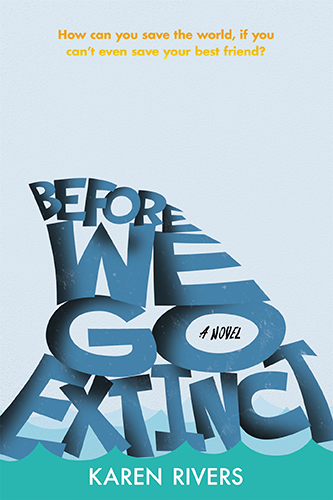

JC, whose friends call him Sharky, is a teen just ready to begin his final year of high school. In the past, he’s been a risk-taker enjoying skateboarding and parcours around Brooklyn. When his friend falls from an unfinished building during one of these adventures, what Sharky assumes is a terrible accident leaves him heart-broken. This energetic and athletic young man wants only to stay in his room, watch documentaries over and over, and send texts to his dead friend. He completely refuses to speak. Unable to deal with her son and finding communication with him next to impossible, Sharky’s mother decides to send him to an island off the west coast of Canada where his dad is a caretaker. There is virtually nothing at all on the island, and so Sharky can spend time with nature and with the only other family there, a woman and her two children. Rivers gives her readers an interesting main character in Sharky, and they can watch him try to process the terrible grief he feels. For nearly half of the book, he does not speak at all, but readers are able to understand his thought processes as they make the grief journey with him. Much of what Sharky does seems futile. He texts his dead friend frequently. He composes many emails to Daff, a girl whom he alternately seems to love and to hate, but he never sends them. When he receives messages from Daff, he replies in a few words of French or not at all. In other words, Sharky’s only true communication is within his own mind. Sharky’s father has not been the best role model, and it takes some time for the two to understand and accept one another. At first, his father attempts to fill the communication void with a great deal of chatter, but later he comes to understand his son better and gives him the time and space he needs. The other family helps Sharky reconnect with himself, particularly as he begins a tentative relationship with Kelby, the daughter. She and her younger brother Charlie encourage Sharky to come out of the shell which his grief has imposed on him. Some young adult readers will identify with Sharky, and perhaps this book will help them with their own struggles with grief. Others may find the novel too introspective since much of the story takes place only in Sharky’s mind and there is very little action within the plot. The setting of the island illustrates the isolation felt by Sharky and allows the author to add information about sharks, diving and climate change. While these are interests of Sharky, they don’t add a great deal to the plot. In Sharky’s mind, he wasn’t able to help or save his best friend, and so he wonders about attempts to save much bigger things, such as the planet itself, before creatures such as sharks become extinct. Like anyone dealing with grief, Sharky’s progress is slow, and much of the story is taken up with his meandering thoughts about what he should or shouldn’t do. At the end of the book, readers feel Sharky has come to some understanding and acceptance, but Rivers does not present any magic solutions. She understands that life can be difficult and that there are obstacles which often seem impossible to overcome, particularly when you are a teenager striving to become your adult self. The cover of the novel mentions that ReaLITy titles are “pathways to discussion about topics that impact the lives of today’s young adults”. Certainly the loss of friends and loved ones is a topic worth study, and Before We Go Extinct may be the pathway for some readers to better understand and deal with their own grief. Recommended. Ann Ketcheson, a retired teacher-librarian and classroom teacher of English and French, lives in Ottawa, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- May 27, 2016. |